A vote that will fundamentally shift the classification process for high schools is coming on Sept. 16. But ahead of a special session of the CHSAA Legislative Council, the schools that are being affected are calling on the membership to vote down ADM-3 so that more dialogue can take place ahead of complete shift in CHSAA’s classification process.

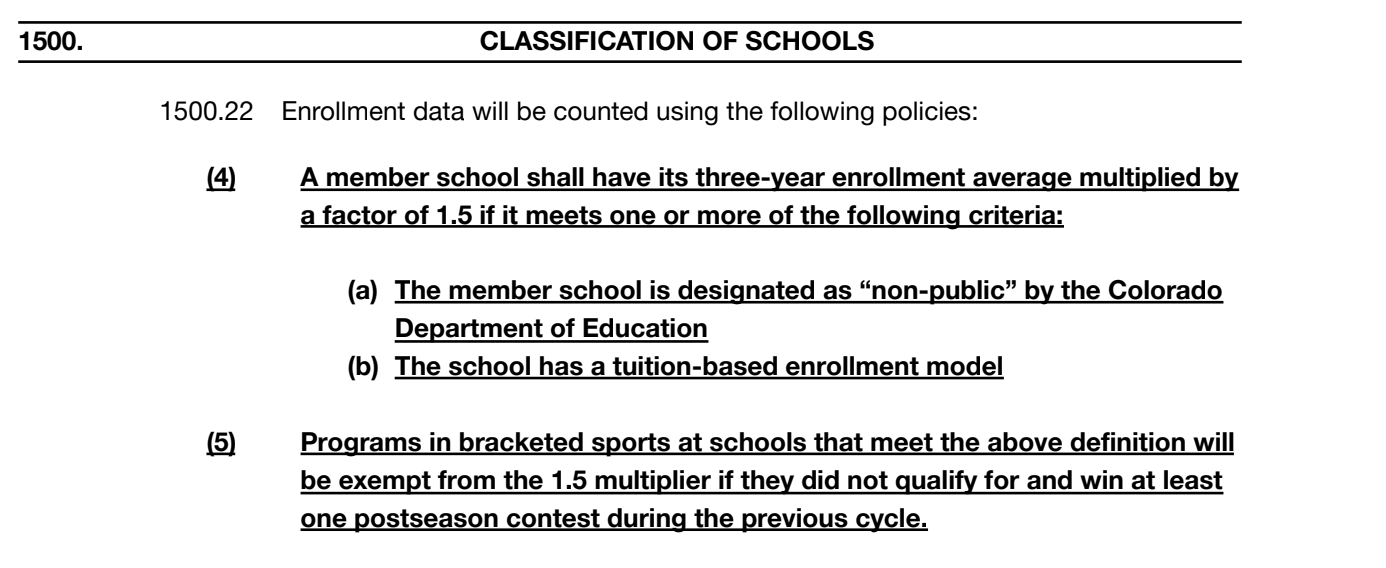

ADM-3 is an administrative proposal that was sent to the CHSAA Board of Directors from the Classification and League Organization Committee (CLOC), via a classification task force. It calls for a 1.5 multiplier to the three-year average of enrollment numbers that Colorado Department of Education defines as non-public. The proposal reads as follows:

The rationale, as outlined in the proposal (which can be found in the Legislative Council Packet) states: “The multiplier is intended to adjust for the competitive advantages that some member schools may have due to selective admissions, enrollment controls, and/or tuition-based enrollment when compared to schools which do not have these advantages. The multiplier aims to standardize data and ensure a more equitable comparison of school enrollments despite differing admission practices. A 1.5 multiplier is a common and widely accepted factor used by other state high school associations that have implemented similar models. Using this figure allows Colorado to align with a known benchmark while still tailoring the system to CHSAA’s needs. A 1.5 multiplier increases adjusted enrollment meaningfully by 50% without automatically forcing all affected schools into a higher classification. It provides enough impact to potentially change placement without guaranteeing it, which maintains fairness and prevents overclassification while ensuring equity without a full separation for post-season competition.”

As pointed out in Line 5, programs in bracketed sports (team sports such football, soccer, baseball, basketball, etc.) that meet the definition of a “non-public” school will be exempt from ADM-3 if they do not qualify for and win a postseason contest during the previous two-year cycle.

This is a fight that has been brewing in Colorado for decades and a fight that is hardly contained to the Centennial State. Various states have tackled the public vs. private issue in different ways – including an enrollment multiplier – and Colorado schools have finally forced the issue to ahead.

(Dan Mohrmann/ColoradoPreps.com)

With less than a week ahead of the vote, some private schools have appealed to the CHSAA membership to shoot down the proposal. They cite a list of concerns that they have with ADM-3, including the idea that the proposal was rushed into a forced vote and flawed data surrounding a perceived advantage that private schools have. But according to those involved with the process of getting ADM-3 in front of the Legislative Council, this issue has stemmed from years of discussion and pleading from the membership to address an issue that they feel has gone unchecked as other states around the country address it in various ways.

Classification Reboot

The science of classifying schools in Colorado has been inexact for decades. The oft used figure for classification has been a school’s enrollment and programs have had the ability to appeal in order move down to class where they feel they belong.

A big red flag came in recent years when initial classification splits and placements were released and the CHSAA office received approximately 300 appeals for what would eventually be the 2024-26 cycle.

Part of the problem was that the enrollment numbers being used were nearly two years out of date by the time the cycle had started. Those enrollment numbers were a self-reported number from the schools to the CHSAA office in October. When CHSAA compared the numbers they received to the numbers released by the Colorado Department of Education, some of the enrollment figures were off. Some by a few and some by a few hundred. For private schools, they are not required to enlist their enrollment numbers to CDE, so the only enrollment number they report is to CHSAA as outlined in Bylaw 1510, section (e).

The system was broken and needed to be addressed. A classification task force was created and served as a sort of sub-committee to CLOC. Some of the streamline measures they addressed were getting a more accurate enrollment figure and using an average of three years of enrollment rather than a single figure.

But while enrollment was being addressed, the membership was pushing to bring the topic of public vs. private into the discussion.

“I was a part of the CLOC task force and it was a big part of that as well,” Kit Carson athletic director Sara Crawford said. “When I was part of that task force, I felt like I was representing a wide variety of smaller rural schools. That’s what kept coming back was private vs. public so we knew that something needed to be done because that’s what we were hearing.”

As an educator of over 30 years, this was not the first time that Crawford had heard the call to address the issue. She had talked with several administrators from other states who had tackled the issue. She said that an administrator from Texas had joked that “you should just do we do and have public school championships and private school championships.”

No one to this point has felt that to be a necessary option. Given that the combined number of public and charter schools (if charter schools were to also be split off), it would branch off fewer than 90 schools with enrollment ranging from 16 (Shining Mountain) to 1,710 (Regis Jesuit).

When it came to the overall topic of classification, especially concerning specific schools, the task force was hearing from its constituents and impactful legislation was on the horizon.

ADM-3

Depending on perspective, the drafting of ADM-3 and sending it to a vote has either been a long time coming or was an incredibly rushed process. Crawford maintains that throughout the entire time she served on the task force to examine classification from a larger perspective, there was a push from the schools she represented to bring the private vs. public battle to the forefront.

From the time the task force was formed to when legislation was actually getting sent to the Board of Directors and then out to the membership was a span of about two years.

The other impactful piece of legislation was ADM-4, which would have placed dominant programs up a classification. The definition of a dominant program in ADM-4 was winning three state championships in four years and in the most recent season, making the semifinals (in a bracketed sport) or finishing in the top four of team scoring (in a non-bracketed sport).

ADM-4 passed an April Legislative Council vote 38-33 with one voter abstaining.

Prior to that Legislative Council meeting, the first version of ADM-3, which included charter schools, was tabled for further discussion. Both proposals called for a change in the classification system, but through two very different means. At no point, were the two proposals looked at as a package deal. They discussed and drafted separately.

“We sat down and looked at (the proposals) separately, and for a long time,” Crawford said. “It took us about two years to get through all that and then we looked at them together.”

The process to draft the legislation and present it to the Board of Directors in order to send it for a vote began in October of 2023 and came to ahead after the January 2025 Legislative Council meeting when schools got word that the original draft ADM-3 was coming.

“We were in a league meeting and our Board of Director rep (Niwot athletic director) Joe Brown let us all know, just in a quick 10, 15 seconds, that the board was going to put something forward,” Holy Family athletic director Ben Peterson said. “Probably a month later, we got the actual bylaw.”

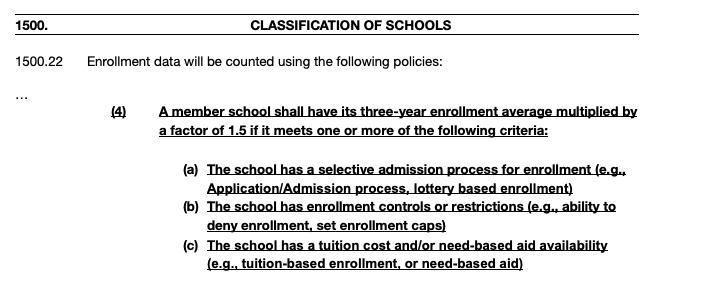

In the first draft of ADM-3, the net was a lot wider when it came to which schools would be affected. Selective enrollment and enrollment caps were a piece of that legislation, which meant that charter schools were going to meet the standard, as well as private schools.

(Original version of ADM-3)

Selective enrollment is one piece of this process that the private schools took umbrage with because of Colorado’s status as a choice state. In a letter that Peterson wrote to the membership, he identified enrollment control as a benefit enjoyed by the private schools, but offered a quick counter.

“All schools in Colorado, as a byproduct of open enrollment, have this ‘advantage,'” he wrote.

Although it should be noted that public schools cannot deny enrollment to any child living in their district/school border while private schools can deny enrollment to any applicant.

When the ADM-3 was pulled from the April Legislative Council meeting, it was a clear indicator that more work needed to be done. A Multiplier Solutions Team was formed with the intent of clearing up the language of the bylaw, which many felt was vague.

“I agreed that we needed to change some things with it,” Crawford said. “It wasn’t quite right.”

The team was comprised of 14 members, eight representing public schools, four representing private schools and two representing charters.

On one side, there was appreciation for the input that went into clearing up the language and coming back with a more concise version of the proposal that provides a direct outline as to who would be affected. Charter schools were no longer impacted as a result of the language.

Others still felt that true discussion hadn’t taken place to create a piece of legislation that made sense for the entire state.

“We met one time in May for three hours,” Peterson said. “That’s not a task force. That’s not a committee. It was a chance for people to have their voices heard a couple of times and then the new bylaw gets sent out in August and it says this is what everybody agreed on. No it wasn’t.”

The Data

Throughout the process, the biggest request has been the availability of data that shows private schools having a distinct advantage in completion. CHSAA compiled championship data initially, then expanded the scope to include overall postseason figures. The numbers were given to provide the membership with information as the CHSAA staff has no vote within the Legislative Council and has no preference in Tuesday’s outcome.

The broad stroke of the argument is that looking at state championships won since 2020, private schools make up about 10% of CHSAA membership, but won over 20% of the state titles. The measurement is compared to what the data refers to as “expected championships” which says “if a group of schools is 10% of the schools within a sport and classification, they would be expected to win 10% of championships.”

The overall number was provided as well as a breakdown of championships per classification. Class 3A saw the biggest concentration of private school championships at 35%. The private school membership in 3A is listed at 9.63%. Class 4A saw the smallest percentage of private school champions (15.06%) with a private school membership slice of just under 5%.

The private schools see major flaws in the data and don’t think it provides a justified vote for a multiplier.

“They took [the data] and just said that 78% of the schools are public; they took the percentage of the schools and 78% of the schools are public so they should be winning 78% of the championships,” Lutheran assistant athletic director Dylan Johnson said. “That is flawed in itself. No school is going to win its stakehold in the membership. That would make the argument that everyone is equal and everyone should have a championship. That’s not how athletics work.”

Like Peterson, Lutheran athletic director Rachelle Robbins sent a letter to the membership and used a specific example of a dominant public school program to point out their perceived flaw in the information provided by the CHSAA office.

“Take Cherry Creek as an example: one of approximately (60) 5A schools that participated in boys tennis (2024), has won the past 5 state championships, far more successful than ‘expected,'” she wrote. “Under the logic and data CHSAA used as rationale for this amendment, Cherry Creek Boys Tennis should win 1 of every 60 state championships. Success in athletics is not spread evenly by percentages — it clusters with strong programs, coaches, and communities. Using this logic against non-public schools sets a precedent that could just as easily be used against dominant public schools.”

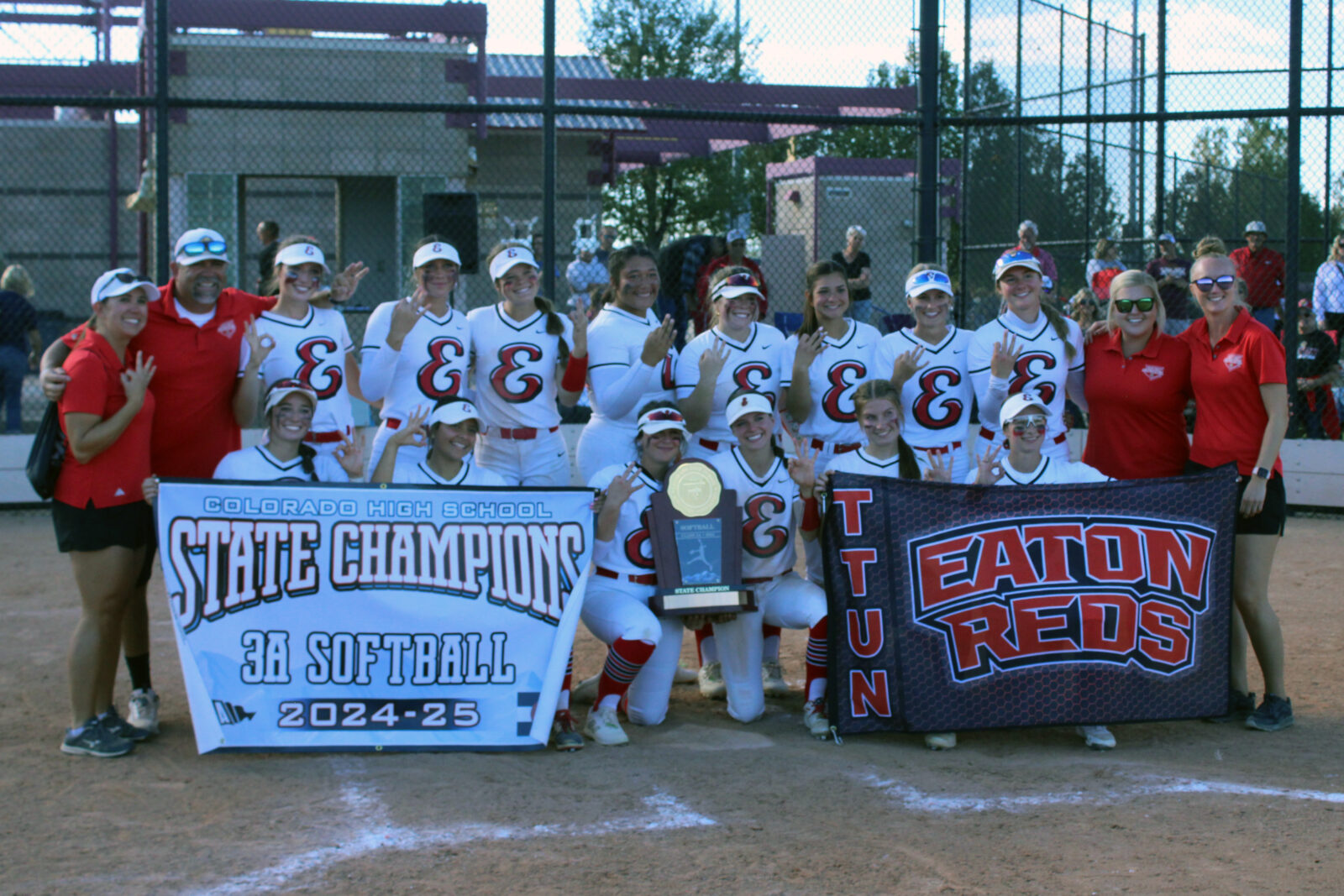

(Dan Mohrmann/ColoradoPreps.com)

But the data was never intended to be applied to specific elements within the groups. Instead, it was designed to paint a larger picture that could identify trends within certain groups. In a debate such as this, this kind of data can either reinforce long-held beliefs or identify a clear bias or ulterior motive.

“(CHSAA) spent a lot of time going through and pulling numbers,” Crawford said. “And when you talk to people [this issue] is about postseason. People will bring up specific names of schools and it’s the schools that are involved in postseason.”

Peterson looks at the data and doesn’t come to the same conclusion that the public member schools talking with Crawford and other board reps are coming to.

“There are pie charts and bar graphs and stuff like that and to me that’s not proof that we need this bylaw,” Peterson said. “That’s part of it. A small part of, but it doesn’t prove anything that this is the correct bylaw or the right thing to vote on at this time.”

The data also showed that charter schools make up about 12% of the membership and accounted for just 6% of state championships, which was a factor in changing that language to not include them.

ADM-4

Perhaps the biggest slight that the private schools feel is with the passage of ADM-4 last spring and the way that it defines a program that needs to move up a classification.

Winning a state championship, even for premier public schools like Cherry Creek or elite private schools like Valor Christian, is difficult. ADM-4 says if a program wins three championships in four years and reaches the semifinals in the most recent season, it moves up a classification.

(Dan Mohrmann/ColoradoPreps.com)

Examples of programs facing that outcome would be both Eaton and Lutheran softball. One public school, one private school. With a 6-man football title, Stratton would then fit the criteria to make the jump to 8-man. Kent Denver boys tennis could reach the semifinals of the team dual tournament which would then bump the Sun Devils to 5A.

Those programs, both public and private, have done the work at a level consistent enough that a jump in classification feels warranted.

The private schools maintain that a passage of ADM-3 changes the definition of a successful program for them, singles them out and creates a double standard.

“Three state championships and either a runner-up or Final 4 in the fourth year, that’s a significant amount of winning,” Peterson said. “But now we’re saying a private school is successful if they get to the playoffs and win one game. That’s so far off, I don’t even know who you can look in the mirror and say these are the same thing.”

There is no language in ADM-4 that exempts any school (public, private or charter) from a jump in classification.

But the added language of ADM-3 (Line 5) was actually put in place as a method of protection from struggling private school programs. According to Crawford, the membership was insistent that the public vs. private issue be addressed in classification. Once momentum built for the multiplier, it was tough to get that toothpaste back in the bottle.

But rather than placing a sweeping multiplier on all programs in all private schools, it gave struggling programs a reprieve from being placed in front of competition from higher enrollment schools.

“That, to me, helped a lot,” Crawford said. “I’m friends and acquaintances with many of the ADs who are with schools that are non-public. I listened to concerns from them too and it made a lot of sense. Not all private schools are the same, just like not all public schools are the same. To group them all in there and not have anything about success in there, that would have been unfair and not right.”

And that’s where the debate picks up steam. With a standard of success already defined with measure in place to move up programs deemed dominant, why does ADM-3 need to go into effect at all?

Both Lutheran and Holy Family, speaking for themselves and not on behalf of all private schools, say institutions like theirs are being held to a different standard before a standard already voted into the bylaws has had a chance to take shape.

“If we’re talking about competitions, why is there a different threshold to make that happen,” Johnson said.

He later continued when asked about alternative ways to classify schools and programs so everyone feels like they’re on a level playing field:

“I would love to see what happens over the next two-year cycle with the Dominant Programs Placed Up (bylaw),” he said. “We should let that take place. It was voted on and passed by the membership. The more we can let things that the majority passed take place, look at it, did it work, does it need to be modified? That is a good starting point.”

Moving forward

Regardless of the vote’s outcome on Tuesday, the public vs. private school debate is likely to rage on. Different states throughout the country take different approaches when it comes to public and private institutions. Texas splits them up entirely with different associations governing each side.

At one point, Georgia went the multiplier route, but had different multipliers for different sports and it even hit public schools with open enrollment with those same multipliers. But with Colorado being a full choice state, that’s not a feasible route.

In Colorado, the debate will continue and finding the perfect way to classify all schools and all programs will continue to be more difficult than predicting weather patterns during spring state championships.

In the eyes of the private schools, one thing is for certain: looking at a narrow issue such as private vs. public shouldn’t be the sole factor.

“There are so many things you can look things at,” Robbins said. “Open enrollment becomes a part of that. We have choice school in Colorado. When you start talking about multipliers and things like that, there are more facets to it. If you look at Denver metro area schools as having more resources than people on the [Western] Slope. There are lot more things that go into it than just you’re a private school or you’re a charter school or you’re a public school. There is more to it, and I don’t think any of that has been explored.”

But when it came to the task force and the initial steps in what could turn into a classification overhaul down the road, Crawford explained that the issues discussed and legislation that came out of those discussions was driven by the desires of the CHSAA member schools. The chatter was so insistent that she let it be known that this group wouldn’t be doing the membership justice if they weren’t giving the subject its due attention.

“I was getting frustrated that we weren’t talking about it,” Crawford said. “That was the driving force in my area. It was public, private. Public, private. It seemed like we didn’t talk about it enough.”

According to the CHSAA database, there 37 schools deemed “non-public.” There are 365 total member schools. Colorado Preps had a list of three-year average enrollment numbers for the private schools and using the basketball enrollment splits (because basketball has the most participants and the most classifications), 20 schools would be placed up if they had qualified for and won a playoff game.

(Dan Mohrmann/ColoradoPreps.com)

There is a high likelihood that pass or fail, once Tuesday’s vote is over with, the classification work will continue.

“We are not making the argument that we shouldn’t continue to try and make things more competitive,” Johnson said. “We are not closed off to that. We don’t believe this was vetted enough. We don’t believe this is the answer.”

At least as the proposal currently stands.

Peterson stressed that more discussion is needed before sending forward a bylaw that could drastically reshape the state’s classification system.

“The whole thing just feels rushed,” Peterson said. “This is something that can change the outlook of our association as a whole.”

And he adds there could be unintended consequences similar to what has happened with other legislation that has recently passed.

“This is similar to the shot clock,” Peterson said. “There was no data and there wasn’t enough conversation. If you look back at that bylaw proposal, we said that a shot clock would cost $5,000. Well nobody took into account and no one did the research to look at the cost of actually running the electrical and potentially needed a new scoreboard because the old scoreboards won’t talk to a shot clock. So now it’s going to be at least $50,000 per gym.”

By no means is the shot clock issue and multiplier issue and apples to apples comparison. The point Peterson is making is that a heartstrings could be more complicated than it seems on the surface. Like the shot clock vote, if ADM-3 passes, the membership will move forward with the cards it has been dealt. Like many bylaws that go through the Legislative Council, this result will have its proponents and detractors.

But it will be significant in that the classification process as a whole in Colorado has undergone a transformation and this could be just one step in the evolution.

“I can’t say enough that we are moving in the right direction, not just with this but with some of the other things that were discussed in the past,” Crawford said. “When we were sitting down with people from other states, they were amazed with what we were not doing. So I feel like we’re moving in the right direction.”

Only time will tell regardless of the outcome of Tuesday’s vote.